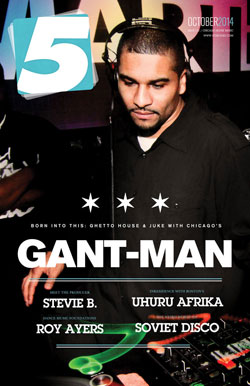

When Gant-Man says that music is his life, it’s more than a cliche. Once the world’s “youngest professional DJ”, he’s since become a cornerstone of the ghetto house and juke scene, breaking the sounds of Chicago to the rest of the world.

I knew the name before I knew what it meant, before his name meant anything to anybody. Even then it was “Gant-Man”, though it could have been “Gant Garrard”.

He has a lot of names but it’s the same guy behind them – a prodigy-turned-trendsetter, a musical encyclopedia who released his first record on Dance Mania before he was old enough to drive.

In certain circles in Chicago, Gant is always going to be the “Youngest Professional DJ”. He’s that guy from the neighborhood, the one that’s always been on the scene – the last and youngest of the generation that made Ghetto House.

In other circles, Gant is practically an elder statesman in the incredibly young Juke & Footwork scene. This often leads to confusion, such as when Gant talks about “the new school” and then has to clarify which: the “new school” in the footwork scene in 2004? the “new school” of Ghetto House and Juke five years before? the “new school” in the early ’90s that took over the House Music scene? Gant’s carved his name in history by having been a part of all three. At the age of 35, he has 25 years of DJ experience and can credibly claim to be more “old school” than many people pushing 50.

At the age of 35, Gant can credibly claim to be more “old school” than many people pushing 50.

Little bits of Gant’s background and his story have come out over time, but nobody’s gotten the entire thing. I’m not sure anybody has really tried. Spanning twenty five years and with a huge cast of influential characters, it’s hard to wrap your arms around it. People do Juke, people do House, and for a large part of the last 15 years, they’ve been two different people and they haven’t had much to say to each other. Except for Gant, who knows them both and better than most, in whose musical mind they’re still largely the same, different dialects of the same common language.

One Turntable & the FM Dial

It happened. There are photographs, there are tapes and plenty of eyewitness testimony. While Chicago artists aspire to lead the world in bizarre entries in the Guinness Book of World Records – a catalog of inane and meaningless “firsts” (the first record, the first label, the first this or the first that) – this one is as legit as they come. At 10 years old I was into Atari and Star Wars; at 10 years old, Gant was launching his career.

“When I first discovered or even conceived of the art of mixing or knew what it was – I’d have to guess I was about 5 years old,” Gant says. “My older brother is 12 or 13 years older than me, and he was into the DJ game back in the ’80s. He knew Pharris, Farley, Tyree and a lot of those guys. When he was out I’d play around with his equipment – you know, tearing up needles on records, figuring out how to move the crossfader. And my mother too – she was the type of person that was buying records and playing them. So there were turntables and crates of records around.”

When his brother moved out, he left a few pieces of audio gear behind. Gant cannibalized a turntable, a mixer and a stereo receiver and put them together in a bizarre configuration. “I played the radio from the receiver, hooked that up to the mixer and the other end to the turntable. With that, I practiced mixing into and out of songs on the radio with the records that my brother and my mother had lying around.”

One morning in June 1989, Gant’s mother told him to get his records together. College radio station WKKC (affiliated with Kennedy-King College) was holding auditions for anybody who wanted to learn assorted jobs associated with the radio industry. Gant-Man was about to go from mixing with the radio to mixing on the radio.

“Now I was young,” Gant says, “but I guess they saw some potential. The program director, a man by the name of James Kelly, took me under his wing. I learned blends and how to count breaks, and months later I was on the air.”

‘Paul’s set-up was like nothing I’d ever seen before. He used one turntable, a mixer and a 4 track cassette deck with pitch control. And with that, he played tracks I’d never heard before.’

Under Kelly, WKKC had gradually increased its power up to 250 watts. Its influence rose accordingly. This was the golden era of Hip Hop and the start of the second wave of Chicago House Music. Its young staff and its South Side audience gave WKKC a jump on these new sounds over its larger, commercial peers on the airwaves.

“That was how I first began to get known,” Gant says. “Besides the audience, WKKC became sort of a DJs’ hangout. There were a lot of people flowing through.”

Gant was ten years old, but it wasn’t a novelty or a publicity stunt. Most people listening had no idea of his real age. One was DJ Paul Johnson.

“Before I met Paul, I knew him from his records and I played them faithfully,” Gant says. “We all did. I was 12 when I first met him. I remember it very clearly because his set-up was like nothing I’d ever seen before. Paul used one turntable, a mixer and a 4 track cassette deck with pitch control. And with that, he played tracks I’d never heard before. No one had. These were tracks that he’d made.

“I was amazed by what I saw and heard, and me being 12 years old amazed him too. He’d only known ‘Gant-Man’ from the radio, and had no idea about my age.”

The Youngest Professional Producer

“Even in the very beginning, before Ghetto House really was a thing, Dance Mania stood for Chicago House Music,” Gant says. “There were a lot of jack tracks. Nothing was polished and everything was underground.

“I heard about Dance Mania like everyone else – just from buying the records, before I produced and before I met Paul Johnson or anybody. Lil Louis’ ‘Video Clash‘ was a record that everyone bought, but it was a few years later when you began to notice that all these other great records were coming from the same label. Records like Robert Armani’s Armani Trax, DJ Rush’s ‘Child’s Play’. Then with records from Deeon, Milton and Paul Johnson and this Ghetto House sound, the name Dance Mania began to really mean a lot.”

That was Gant’s voice on “Trax 4 Da Women” on DJ Lil’Tal’s Flava In Ya Ear EP – a pitch and a half higher than it is today, as it was released in 1994 when he was 15 years old. In 1995 came Basement Trax – The Lost Record Vol III by “Him & I” (Gant and Lil’Tal again). “The Youngest Professional DJ” was the title Dance Mania bestowed upon him for his first solo EP, It’s About Time; and when it dropped, he could make a fair claim to being the “youngest professional producer” too.

“There was a time when all styles of Chicago dance music were really close. Paul Johnson took me to some raves he was booked at in the early 1990s. In that scene, Techno, House Music and Ghetto House were all under the same roof. All of those sounds came together in ‘Percolator’, which you could play in any context – a Techno party, a House set or a Ghetto House party. A lot of those old school tracks from Chicago – by Lil Louis, Mike Dunn, Armando, Robert Armani – were the ones that inspired us to make Ghetto House.

“But as far as Ghetto House, aside from us cats playing it in Chicago – a lot of people weren’t having it. I tried playing Ghetto House in Europe in the late 1990s and they weren’t having it at all.”

160 BPM and Counting

Back in 2007, I interviewed Gant about the launch of his label and some new releases. It wasn’t the first interview I’d done with him. I’ve always liked talking to Gant, because unlike some people who hit you full blast between the eyes with self-promotional hype, Gant can be disarmingly honest. It’s a quality you don’t often find in people who have something to sell.

When talking about the Juke scene in general on that day seven years ago, Gant told me bluntly that it was frustrating to grow the scene because the turnover was so high. Kids would be all about it until they hit 21 – and when they were old enough for the clubs, many of them dropped out. It was always a “young” movement, and it seemed like it would stay that way.

“I remember telling you that,” Gant says today. “And I remember regretting telling you that a few months later, when it all began to change…

“Juke and Ghetto House was largely black music made by black producers,” he explains. “I don’t want to sound exclusionary – I’m just describing how it appeared to us, the people who were making it and playing it.

“It caught on among Latino DJs and a portion of white DJs from mixtapes. But it was the internet that really blew it open. It also showed everyone that this music could be embraced by people from all backgrounds.”

DJs around the world could hear the music on download sites and MySpace. Dancers around the world could see footworkers on YouTube. These were people who didn’t know the music. They didn’t know who made it. They didn’t know us and they didn’t know it came from Chicago. They just knew that they liked it.

In the early part of the last decade, the sound of Juke became increasingly distinctive from ’90s-era Ghetto House – and then it changed again. One of the people responsible for that change was the late DJ Rashad.

“Once Rashad and DJ Spinn got together to make tracks, they did it so, so consistently,” Gant says. “Footworkers were the next generation coming up – the people who are under 30 now. Rashad and Spinn were the leaders of that new school. You have to think: back in the ’90s Rashad had one track on a record with three other producers on it. And suddenly he’s running the new school scene in the south suburbs with a whole new generation coming up behind him. And that marked the beginning – the beginning of what’s going on right now.”

This new, faster style (rising steadily up to 160 BPM) from Rashad, Spinn & Co. was initially embraced on the South & West Sides of Chicago until it was broken across the city by mixtapes and then internationally by the rise of the Internet as a distribution platform.

“Suddenly, DJs around the world could hear the music on download sites and MySpace. Dancers around the world could see footworkers on YouTube. These were people who didn’t know the music. They didn’t know who made it. They didn’t know us and they didn’t know it came from Chicago. They just knew that they liked it!”

Gant & Rashad collaborated on “Acid Life”, which was just released on Hyperdub 10, and in the past on “Somethin’ About The Thing U Do” (Southern Belle). There was anticipation for a huge breakthrough by Rashad & the whole Teklife crew before Rashad’s death in April 2014. It’s a loss that everyone feels deeply, one that’s going to take a long time to come to terms with.

Born Into This

“I don’t want this to sound like a cliche,” Gant tells me, “but this is my life. I was born into it. I’ve never really had a 9 to 5 where I was punching the clock and my name was on a work schedule. It gets hard, no question. I feel like I always have to reinvent myself. There’s always a new generation coming up, and that means a new group of fans, dancers, a new group of DJs and a new group of producers.

“But I’ve seen this music go from something based in Chicago, and here it is, 25 years later and I can play Juke for the crowds. They didn’t want to hear Juke in different countries around the world, but now it’s there.

“My dream,” he says, “is to take both of my crowds – the under-30 people that know me for Juke and the over-30 people who know me for House – and bring them together in one room,” he says. “I don’t know if that will ever happen, but that’s what I dream about.”

Gant & Rashad’s “Acid Life” is out now on the Hyperdub 10 compilation. Hyperdub is also releasing a Teklife compilation, a solo Gant-Man EP and he has a solo EP from Dance Mania coming soon as well. You can reach Gant on Facebook and on SoundCloud.

[…] still remembers the first time he saw Paul Johnson […]

[…] to let your soul glow to the sounds of DJs Hyperactive, DJ Heather, Strictly ’90s sets from Gant-Man and John Simmons, Frankie Vega, Maddgroove and Primary’s Derek […]

[…] John Simmons heard Gant-Man’s Dance Yo Ass Off 1994 mix on Soundcloud, it inspired him to hit his fellow DJ up to collaborate and […]

[…] story short, that was the decision I made. I knew how to make beats, so why not start making House? Gant-Man told me the same thing. “Rondell, if you want to blow up, you need to make your own […]

[…] story short, that was the decision I made. I knew how to make beats, so why not start making House? Gant-Man told me the same thing. “Rondell, if you want to blow up, you need to make your own music.” And […]