The story is so good it could have come from a paperback writer. a group of students in France make a chance discovery of a synthesizer from the late 1960s stored in an old barn.

“Do you recognize this synthesizer?” they ask the internet. The internet, for once, does not.

No one does, and what they’re looking at is a marvelous invention, created by two lost pioneers of electronic music.

The students set off in search of Louise and Marc Voksinski, the “genius creators” of a synthesizer called the LOUMAVOX (‘lou’ise + ‘ma’rc + ‘voks’inski).

(Turn captions on for English subtitles.)

Everyone loves a mystery, and treasure stories, and stories about “lost” pioneers — the kind that dominate music documentaries these days (Searching for Sugarman, You’re Gonna Miss Me, Anvil!, etc.) In just 19 minutes, this impressive film somehow combined all three of these.

The Loumavox documentary had been live on YouTube for just hours when the first reviews came in. A well-known gear site, synthanatomy.com, compared it to synths designed by industry legends Dr. Bob Moog, Don Buchla, Peter Zinoveiff, Alan Robert Pearlman and Dave Smith — “all Synthesizer pioneers who have strongly influenced electronic music and instrument design.” Synth history, however, might now have to be revised to include “two previously unknown personalities: Louise and Marc Voksinski, the developers of the Loumavox.”

If true, Synthanatomy noted, it would be an “historic moment. Not only because of the synth discovery but also because of the developers: Louise and Marc Voksinski.”

They were far from alone. Gearheads began posting it on their pages, in their tweets and appropriating appropriately grainy screenshots for Instagram stories. It was like catnip for the synth community, known for its thousands of amateur scholars and earnest veneration of its history. Here was a new chapter: a device so far ahead of its time it must be the artifact of a time-traveler.

Their enthusiasm attracted some skepticism, most notably from Berlin-based musician and producer Hainbach. He discovered that a website associated with Louise Voksinski in the film — wavesandmind.org — didn’t exist and, according to domain records, apparently never existed (someone has since registered it). Yet the film shows the website and an email from Louise originating from it.

There’s also a photograph shown of Louise with friends in California, purportedly found in the papers alongside the synthesizer. I discovered an earlier copy of the photo posted on numerous sites around the internet, including the blog of food writer Debbie Matthews. The photos are identical, only the one in the film has the face of “Louise” pasted in. I wasn’t able to locate the original source, though the doctoring of a photo that’s been on the internet for at least several years is fairly convincing evidence. Perhaps Louise was shy and the “students” created all this to protect her privacy?

But the creators of the documentary had a bigger problem in that they really did have to show this magnificent device on screen — and what is seen is an absolute anomaly. Prior to the work of Dr. Moog, most synthesizers (probably better called “devices for synthesizing sounds”) couldn’t have fit in the suitcase (an actual suitcase) shown on screen. French electronic music maestro Jean-Michel Jarre is shown on screen in the documentary mentioning how anomalous the device is for its time.

“There are many extraordinary things here,” he says. “The sound of this synthesizer, [and] the possibilities it has, which will be offered only way later with the ARP, Moog, etc.”

Furthermore, the faceplate of the Loumavox shows an anachronistic combination of hand-written labels, period-authentic switches and knobs — alongside what appear to be plastic 3D-printed knobs. Aged and pristine metal are side-by-side, with partially oxidized screws, which would be easily replaceable, fastening the faceplate behind gleaming steel switches, which would not. Such a device would likely be in pieces, not a consumer-ready finished product complete with a tooled casing (though admittedly a collection of transistors and switches would be far less impressive to “discover” on camera.)

But the most anomalous part — the one which made everyone who has worked close to the metal with vintage electronics roll their eyes — was when they finally plugged in a device that had been stuffed into a barn for 53 years and… it turned on. “That one had me laughing out loud,” Hainbach wrote. The components checked out, the lights blinked on and the device began to show signs of life immediately.

It reminds me of a story I wrote years ago about a guy who collects and refurbishes vintage mainframe computers from the 1970s. I asked what was the first thing he does after acquiring one.

“The very first thing? Clean out the nests from things that have been living in it.”

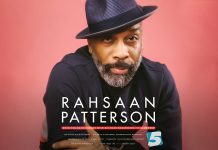

This was originally published in House Music Is Church: 5 Mag Issue #195 with Rahsaan Patterson, Kaspar and more. Support 5 Mag by becoming a member for as little as $1 per issue and get every issue in your inbox right away!

This was originally published in House Music Is Church: 5 Mag Issue #195 with Rahsaan Patterson, Kaspar and more. Support 5 Mag by becoming a member for as little as $1 per issue and get every issue in your inbox right away!

There wouldn’t really be a story here if people hadn’t continued to “investigate” and debate the Loumavox.

But weeks after the documentary was posted to YouTube in mid-December, there was still a lot of speculation not just about what’s real and what’s not, but also among the skeptics about who is behind this and why.

I’ll speculate with them: it’s not a viral hoax for nefarious purposes. I don’t think it’s a shady company attempting to introduce a faux vintage product, or an emulator supposedly based on it, or to astroturf a Kickstarter to cash in on a fairy tale.

I think it’s actually what it says it is: a group of French schoolchildren who brilliantly executed a “mockumentary” — and inadvertently showed how gullible the music gear press can be. It’s a great student film, done so well that many people didn’t just swallow the tale but in some cases were emotionally moved by it.

The “tell” here isn’t really the knobs or the case. It’s that the creators didn’t manufacture very much of the backstory. That suggests a lack of foresight — or the lack of long-term planning that you’d expect from a school project.

The oldest link to the storyline that I could find goes back only a year. This crucial clue actually forms a significant plot point inside the documentary itself.

The creators apparently tried to tie Sisters With Transistors, a documentary that debuted in late 2020, into the story. The Sisters film is the first account the Loumavox creators followed on their Instagram page. Sisters was probably even the inspiration behind Louise Voksinski and her machine — showing the overlooked role of women in an industry that, as Jarre points out in the film and as we’ve noted in past 5 Mag pieces on Bebe Barron, has been quick to make every woman pioneer a footnote in someone else’s (usually a man’s) story. (5 Mag reached out to the filmmakers behind Sisters With Transistors but did not receive a reply.)

In the Loumavox documentary, the students are shown searching Google for the name “Louise Voksinski.” There’s only one result: a comment on a website that reads “Can’t wait to see it ! Does anyone know if they mention a certain Louise Voksinski in the movie ?”

That website in the Google result is still active. It’s scraped from a YouTube upload of the trailer for Sisters With Transistors. The comment was made by “Tuscaloosa,” which is a YouTube account associated with a French band of the same name with multiple live performance uploads on their page. Searching discogs turns up a list of Tuscaloosa band members, one of them named “Franck Dupont.”

Franck Dupont is actually “Franck_D,” shown on-screen as the “teacher” of the students in the Loumavox documentary.

As we watch the students read their teacher’s comment in Google’s search results just moments after the papers and synthesizer have been presented to his class for the first time, we’d have to believe their teacher was a time traveler, or knew the story in advance. Or just tried to plausibly plant a little bit of evidence that Louise Voksinski might have actually existed.

Someone will surely claim that Franck Dupont and the students are themselves actors with some other entity behind them. Comments have suggested the film is an art project to study misinformation, one possibly created by government entities (the Ministry of Culture is mentioned in the film credits.) Synthanatomy, which initially treated the documentary, Louise Voksinski and the Loumavox as authentic, later dubbed it a “synth soap opera orchestrated by an unknown company” with apparently just as much (and as little) evidence.

Loumavox, the forgotten, mysterious Synthesizer. This would be historical synth news… but it looks its a good synth soap opera orchestrated by an unknown company. Thanks @Hainbach101 & @musicthing for your expertise https://t.co/hL6PDXk25p #synthesizer #synth #synthanatomy

— SYNTH ANATOMY (@synthanatomy) December 17, 2021

I doubt it, though. The lack of a manufactured backstory — breadcrumbs that would have been easy and cheap to drop across the internet — throws doubt on the notion of a slick group of professionals behind this.

A slick group of schoolchildren? Now that fits perfectly.

It’s not hard to draw a parallel between the world’s growing embrace of grotesque conspiracy theory in the last few years and the obsession music fans and writers have with uncovering “secret histories.”

o o o

It’s never easy to be that person who thought an Onion story was real.

As speculation increased that the film was fiction and Louise Voksinski never existed, people reacted as they typically do when they’re fooled. Some think it’s funny, some feel embarrassed, still others think it’s a crime.

Strangely, a convincing “mockumentary” like this one often brings out the strongest of all emotions — as if people will carefully guard against believing what they see, or believing what they hear, but are overwhelmed when they have to guard against both.

Some of the outrage though was directed at the gatekeepers — the writers and editors in the media who approached a 19 minute French documentary created by schoolchildren and uploaded by a YouTube account no one had ever heard of before as if they’d uncovered a Minimoog on the altar inside a Pharaoh’s tomb. Making fools of the press was almost certainly not the creators’ intention (we still believe in the innocence of youth), but it did expose a certain credulousness and lack of scrutiny that most of us who read these sites have noticed before. There’s a rhythm to gear news outlets. Most of them seem to compete over who can copy/paste company press releases the fastest. And that makes sense: the users of these sites are primarily consumers, and the sites are mostly about products people want to buy and the companies that made them. (Writing for them, it should be noted, doesn’t pay very well either. It’s a race to the bottom all the way down.) But it’s probably not wise to be prepared to upend history based upon a YouTube video, or to copy/paste ourselves into a hallucination of history rather than the real thing.

That’s an audience problem too. It’s not hard to draw a parallel between the world’s growing embrace of grotesque conspiracy theory in the last few years and the obsession music fans and writers have with uncovering “secret histories.” There are definitely unsung heroes and we find them all the time. But our eagerness to pierce the veil of accepted history can lead us to walk down some very twisted passages and on some perilously narrow branches. It isn’t a big step between “secret history” and “pseudo-history.” It’s probably fortunate that it was only some schoolchildren who made a film that unintentionally exploited these tendencies rather than someone with more sinister motives.

o o o

I sought comment for this story by messaging the Facebook page for the documentary in English and French.

Just before going to press, I received a response, which linked to a video in which the students (and they are students) reveal how they made the film and why. The real story is pretty much what we pieced together here. Here is that video (captions on if you do not speak French):

I felt pretty conflicted about having written this, like anyone who has to diagram an extraordinarily funny joke for someone who didn’t get it. It is better to be in on the joke than to be the one forced to explain it. They don’t laugh when you do. They nod, and the next thing they do is tell you why the joke wasn’t funny in the first place.

And to be clear, I’m not saying this is a joke. The students and their teacher did an extraordinary job here, making a film that’s actually worthy of the fictitious synthesizer and its make-believe creator. To Franck Dupont I also sent a message I hope he shares with his students: “Great show!”

Photos mostly taken from screenshots from the documentary.

There’s more inside 5 Mag’s member’s section — get first access to each issue for only $1/issue.